By Pierre Lévy

Probably, the first weeks in the office of a US President have never unleashed a global shockwave of such magnitude. Explanations, decrees and provocations follow one another in rapid succession: declarations of ambitions vis-à-vis Panama, Greenland and Canada; projects of “purification” and takeover of the Gaza Strip; almost complete closure of the USAID; tariffs in all directions. And this could only be the beginning.

The European Union is not spared. Most of its leaders are in a state of shock, horror and despair. Everyone knew that the hypothesis of a comeback by Donald Trump to the White House could cause chaos. But no one had anticipated it to this extent.

In France, Germany and other European countries, the mainstream media join the chorus. Expert analyses, columns in the press and talk shows on television multiply. With a refrain: How can the leader of the Western world, our big brother, treat us so badly? With such impertinence! And that – as an added difficulty – exactly at the time when the Atlantic Alliance should be more united than ever, in the face of Russia’s advance on the Ukrainian front, which threatens the Old Continent. A leitmotif that torments the western elite.

In this global abyss, the western elites seem to be clinging to a magical idea: Washington’s bad manners could trigger a boost in favor of European unity and a integration process that has so far stalled or even regressed. Actually, there are no concrete signs in this direction. Some capital cities like Budapest or Rome, even Bratislava and perhaps soon Vienna and Prague, show a growing dissent against Brussels.

But the European propaganda machine is running at high speed: in the face of the US, which one can hardly rely on or even seems aggressive – especially in trade –, it will become all the more urgent to promote a “European sovereignty” (an oxymoron that Emmanuel Macron has been promoting for years) and thus strengthen the integration of the EU.

Coincidentally, this falls exactly on the fifth anniversary of the Brexit. This has given official commentators the opportunity to multiply analyses and reports that show how the economic situation in the United Kingdom has deteriorated – a falsehood, if one compares it with many countries of the European Union – and above all, how the British would regret their decision. This assertion is particularly questionable, especially considering that the opinion poll institutes that make this claim are the very same ones that predicted a defeat for the Brexit supporters in the June 2016 referendum.

Whatever the case, the false self-assurance that “we are stronger together” is coming back in the pro-EU propaganda. The formula seems reasonable. In reality, it is dangerous and false.

Dangerous, because it, in the name of power and efficiency, lets the freedom of each country be forgotten, its own political decisions to be taken. The principle of integration consists in setting an ever-tighter framework, outside of which every decision is forbidden.

This applies to the economy: liberalism, market and competition must remain the rule; this applies also to international trade (Brussels has the monopoly of trade agreements with third countries); so does it apply to the currency (the ECB is “independent” and decides alone on monetary policy); one could also mention taxation and migration policy.

Although several of these frameworks are imploding under the pressure of objective contradictions between the member states. But the rules and sanctions remain in place.

However, some could argue that the efficiency and collective power make it worth sacrificing national sovereignty – the sovereignty, that is, the freedom of each people, which it chooses from among its preferred directions.

This is the situation that has been prevailing for years: especially in France, the voters abstain, the majorities follow one another, change or disappear, but the great decisions remain the same. This leads to a severe crisis of democracy.

But is this at least in some way efficient? The results do not suggest so. After several decades of the single currency, the stability pact, the common economic governance, the budget oversight by Brussels and the “structural reforms” that target social achievements (labor market, pensions, etc.), the European Union is one of the regions of the world where growth is at its most catastrophic and industry is disintegrating. So much so that its leaders themselves conjure up the specter of a “slow agony”.

In another area, the deregulation imposed on all member states has introduced competition in public services, especially in the fields of telecommunications, rail transport, energy, etc. Especially in the latter, the damage is immense and the users pay the bill.

Furthermore, the uprisings of farmers in various countries, triggered by the recent signing of the free trade agreement with the Mercosur, illustrate how harmful the exclusive negotiation power of the European Commission is.

In reality, the interests (as well as the economic configurations and political cultures) of the various states are multifaceted, sometimes even divergent or contradictory. The attempt to “put all in the same pot” necessarily goes at the expense of the most. Union does not make strong, but weak.

Here is a perfect counterexample: Switzerland. This small country has so far refused to join the EU (despite the efforts of a part of its ruling class and Brussels) and defends its sovereignty. Its economic performance can make the envy of most of its neighbors. The preservation of its freedom of action undoubtedly contributes to this.

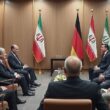

A freedom of action that also applies in diplomacy – where the European framework hinders the implementation of independent national foreign policies. By the way, the 27 could not even take a common position in the face of the provocations of President Trump on the future of the Palestinians.

The problem is not this inability of the community, but the prohibition that this or that country cannot take its own path. Paris would thus not be able to pick up on the “Arab policy of France”, which, under the presidency of General de Gaulle, was launched half a century ago and then abandoned.

The next few weeks will confirm how unlikely it is that the EU will find the way to unity thanks to the “Trump threat”. But it is certainly useful to remind that this hypothetical unity could lead to an additional damage..